An above-the-field campaign

Lauren Smith

Sep 4, 2024

Source: Brent Peterson

In the sky over Oklahoma farm fields, a giant helium balloon floated. Attached to its tether was an instrument built in Doherty Hall.

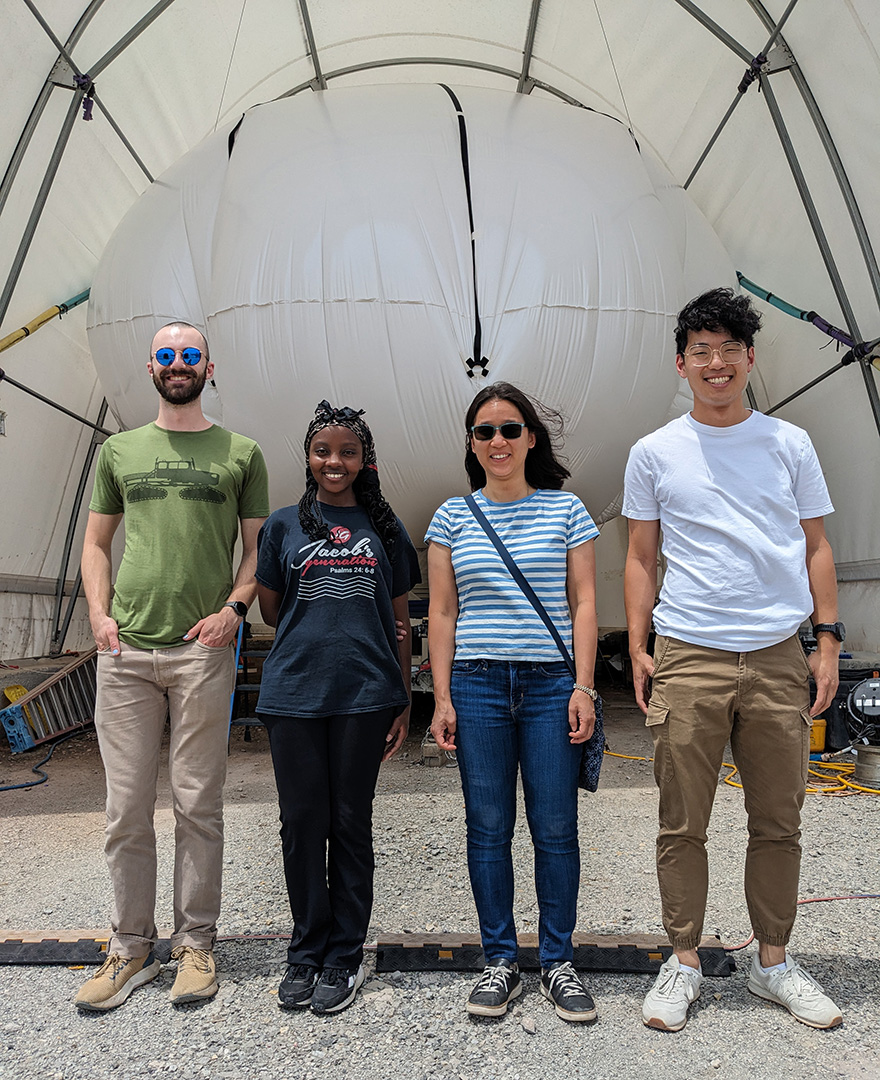

Coty Jen and her research group traveled to the US Department of Energy's Atmospheric Radiation Measurement Southern Great Plains (SGP) observatory in Oklahoma for a six week field campaign. SGP is the world's largest and most extensive climate research facility. The Jen Lab and collaborators from Sandia and Brookhaven National Laboratories were there to conduct the first vertically resolved sulfuric acid measurements. These measurements were possible because of the portable, battery-operated instrument the Jen Lab designed and built.

The goal of the research is to understand how aerosol particles form at ground level compared to how they form up to one kilometer above the ground. This information will improve models of the Earth's climate.

"There are a lot of uncertainties in how much solar radiation is being reflected or absorbed from clouds. A lot of that comes down to not understanding or being able to correctly model aerosol particle concentrations throughout the atmosphere," says Dom Casalnuovo. The Jen Lab is working to fill those gaps in our understanding.

Most existing measurements are at ground level, even though a lot of nanoparticle formation is likely happening higher up in the air. Taking measurements above ground level is challenging. Current approaches require expensive and heavy equipment on a plane or blimp. The Jen Lab is developing equipment that makes taking measurements more accessible. "As chemical and mechanical engineers, we want to create a solution that is more available to other labs, in terms of equipment and cost," says Casalnuovo, a Ph.D. student in chemical engineering.

Smaller equipment that can be used on a tethered balloon is one example of how the Jen Lab designs instruments to measure previously undetected compounds in hard-to-reach regions of the planet. Compared to other equipment, their instrument to measure sulfuric acid is lower cost, more portable, and better designed to operate in the harsh conditions often present in these hard-to-reach regions.

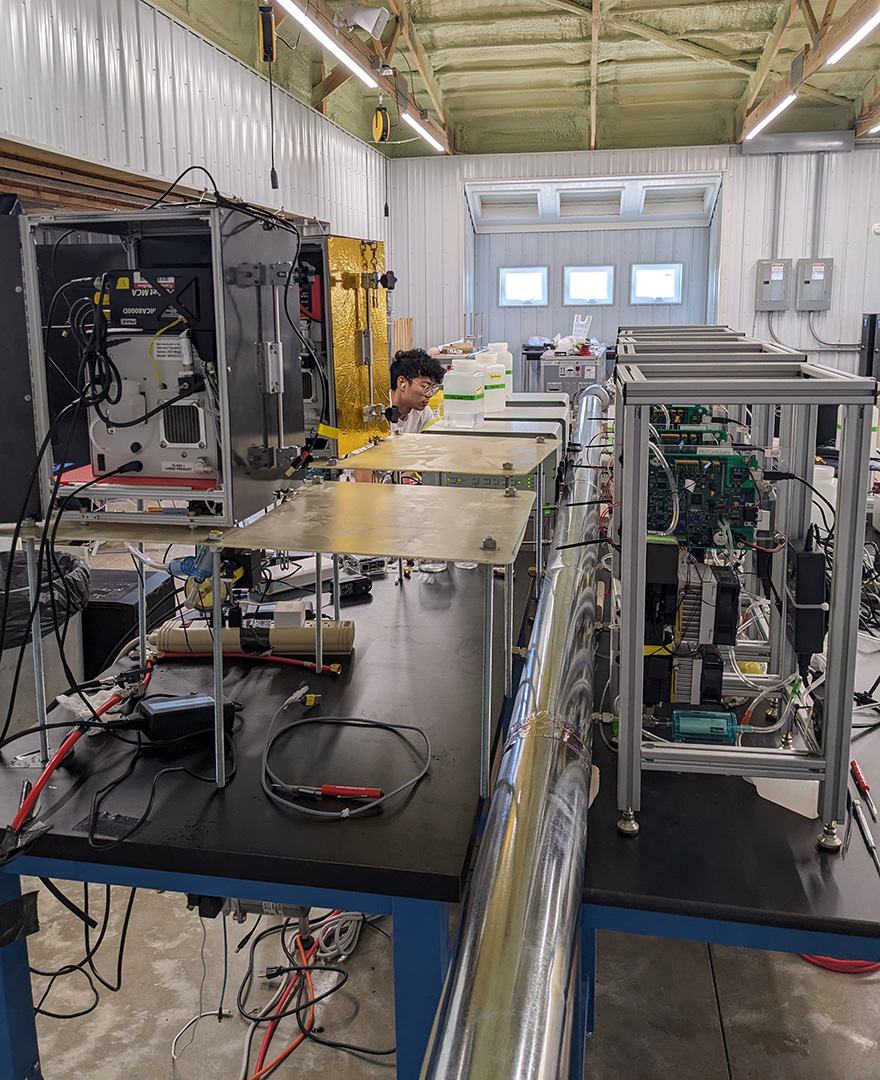

Jen, an associate professor of chemical engineering, spent the past few years preparing for the Southern Great Plains campaign with her students. In addition to preventive maintenance to get their equipment in the best shape, they brainstormed what might go wrong in the field and came up with solutions. "When you take equipment out of a lab and into a non-ideal environment, there are new and greater challenges," says Casalnuovo. To test their equipment, the Jen Lab conducted field campaigns in Pittsburgh, and Casalnuovo traveled to the Southern Great Plains site for a two-week campaign last summer. In the immediate lead-up to this summer's campaign, Jen and her students packed up almost all their equipment, including two mass spectrometers to measure trace gasses in the atmosphere. Fourteen particle counters were also deployed by Jen Lab member Darren Cheng, a Ph.D. student in mechanical engineering, to measure fast-evolving changes in atmospheric particle concentrations.

Field measurements aren't as simple as putting instruments outside. Many things are changing at once, including the weather, amount of sunlight, meteorological conditions, chemistry, and source emissions. During the Jen Lab's six weeks at the Southern Great Plains site, spiders made complex webs in their instruments' sampling tubes, and farmers started harvesting wheat in the surrounding fields. Some farmers burned their fields, and that changed what was in the atmosphere, depending on whether the research site was upwind or downwind from the fire.

Hot temperatures and strong winds in June brought other challenges. Flight time was limited by extremely high winds, and a heat wave forced the tethered balloon operators from Sandia National Laboratories to start flying in the pre-dawn hours. With daytime temperatures above 100 degrees fahrenheit, Casalnuovo placed ice packs inside the thermally shielded box protecting the instrument before sending it up on the balloon. He also removed some panels for better ventilation. Even so, the instrument temperature neared 122 degrees fahrenheit. "There is a lot of work we need to do in the lab to figure out what the data means given that the electronics were that hot," says Jen.

The Jen Lab is analyzing terabytes of data. In addition to their own measurements, they have access to atmospheric radiation and meteorology measurements from SGP. "Comparing our measurements with those meteorological conditions will give us a much better understanding of how aerosol particles and gasses travel vertically throughout the region," says Casalnuovo.

After hot prairie winds, the Jen Lab welcomes its next field challenge: cool ocean breezes. They are already at work making the thermal shield boxes used in Oklahoma more water tight, to protect the instruments from sea spray aerosols. Next year, they will trade balloons for boats to transport their instruments and take measurements over the Gulf of Maine.

For media inquiries, please contact Lauren Smith at lsmith2@andrew.cmu.edu.