Measuring ocean air to understand clouds and climate

Lauren Smith

Jun 25, 2024

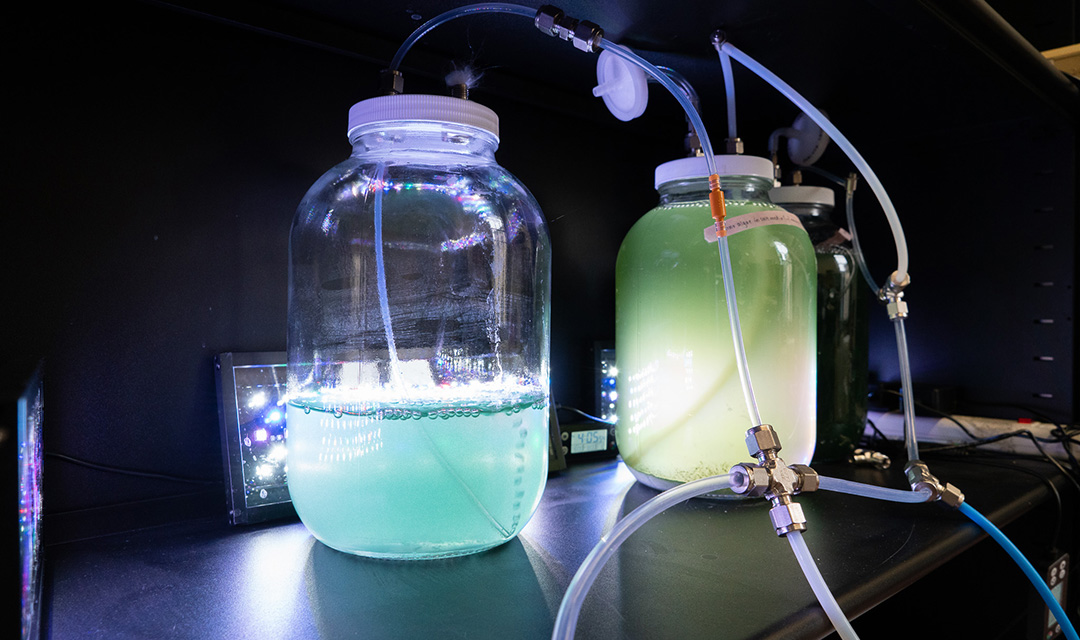

Jars of algae in the Jen Lab

Coty Jen is working to understand how the fastest warming part of the ocean—the Gulf of Maine—is affecting the atmosphere.

"Oceans cover about 70% of the planet's surface area, so what's happening over the ocean is quite important for how the climate is evolving," says Jen, an assistant professor of chemical engineering. "There's a lot the scientific community doesn't understand because it's difficult to take measurements over the open ocean."

A hallmark of the Jen Lab is that they design instruments to measure previously undetected compounds in hard to reach regions of the planet. Jen received funding from the National Science Foundation to study marine phytoplankton emissions and their impact on atmospheric chemistry.

The project connects to Jen's research on emissions from harmful algal blooms. Although freshwater covers much less of the planet's surface than oceans, more people live nearer to it. "We suspect emissions from freshwater algae are quite similar to emissions from marine phytoplankton communities," says Jen.

Both projects combine lab and field work. To study marine emissions, the Jen Lab has designed controlled experiments to grow specific phytoplankton strains and then stress them in ways similar to how the ocean is changing. Examples of stressors include increasing the temperature, changing the acidity of the water by adding more carbon dioxide, or cutting off the light source. Jen is trying to understand the bounds of the emissions from a limited microbial community.

With samples of water from the Gulf of Maine, Jen's research group will also study emissions from ocean water in the lab. The results will constrain what they should expect to see during their field work.

In a collaboration with Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, the field work will couple ocean and atmosphere measurements. Bigelow brings expertise in water chemistry and will measure pH, the biogeochemical parameters of the ocean, and the distribution of phytoplankton, bacteria, and fungi. Jen is traveling to the Gulf of Maine next spring to take atmospheric measurements. Anticipating seasonal differences, she will return the following fall.

The Jen Lab will deploy a set of instruments onto the Bigelow dock, passenger ferries, and Bigelow research boats. This includes mass spectrometers, as well as two instruments developed in the Jen Lab: one can measure the tiniest atmospheric particles at high time resolution, and the other can measure sulfuric acid in the air.

She is interested in how microbial communities in the ocean emit compounds into the atmosphere. These compounds affect aerosol nanoparticles, cloud formation, and ultimately how quickly the planet is warming due to greenhouse gasses. Jen is particularly interested in the atmospheric particles that often become clouds. "Because oceans are darker, they absorb more radiation than land when they are not covered by clouds. Therefore, clouds that cover the ocean cool the planet more than clouds that cover land," she explains. The more we know about how marine emissions influence atmospheric chemistry and cloud formation, the better we will understand climate change.

For media inquiries, please contact Lauren Smith at lsmith2@andrew.cmu.edu.