A nanosnag with a big effect

Lauren Smith

Mar 4, 2025

Source: Jim Schneider

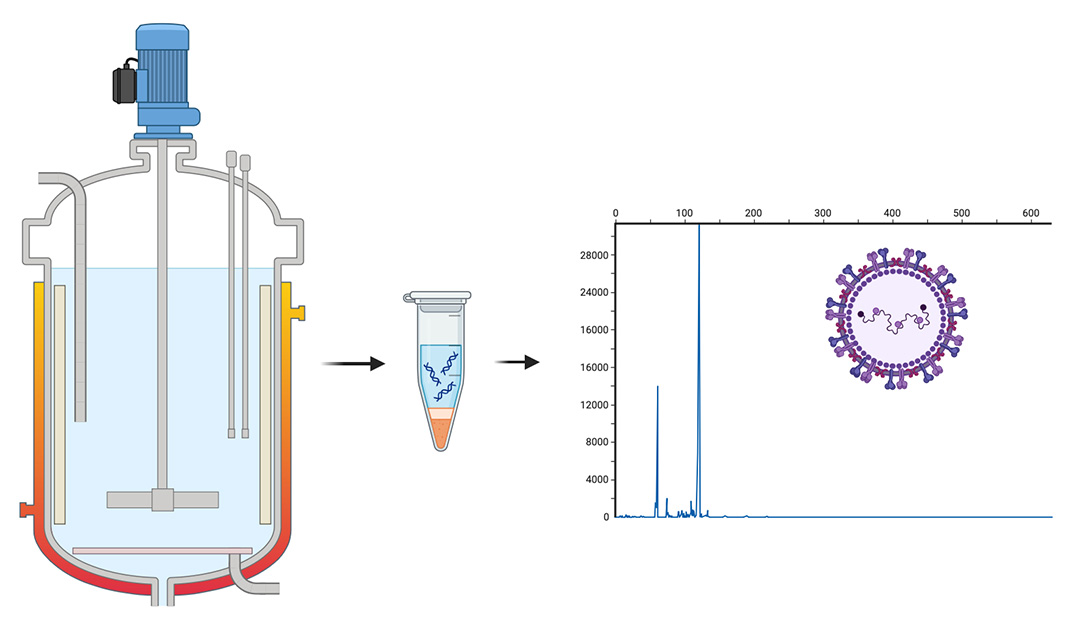

As viral vaccines are increasingly used to meet global health needs, the pharmaceutical industry is manufacturing larger amounts of virus to make them. A new method of virus detection from researchers at Carnegie Mellon University is poised to improve quality control in vaccine manufacturing by rapidly quantifying viral genomes in samples taken directly from bioreactors.

Research from the Schneider Lab has uncovered a new mechanism of electrophoresis that attaches a very short piece of double-stranded DNA, which they call a nanosnag, to a viral genome. "The nanosnag slows down the genome as it moves through a gel-like matrix in the presence of electric fields. This abrupt slow-down concentrates the genomes in a sharp band that confirms that the viral genome is intact and tells us how much of it is there," explains Jim Schneider. Despite the slow-down provided by the nanosnag, the 10-minute runs are very fast compared to gel electrophoresis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or other methods used to assay DNA. This is because Schneider's method uses surfactants rather than polymers as a gel-like matrix.

Polymers such as those used in gel electrophoresis have long-lived crosslinks that the DNA has to move around. That creates a sieving process that separates DNA based on length. Schneider, a professor of chemical engineering, has spent many years developing electrophoresis methods for separating DNA. The crosslinks in the surfactant systems that Schneider uses don't live as long, so while they are effective they allow long DNA or RNA to pass quickly.

In his earlier work with short DNA targets, Schneider developed micelle-tagging electrophoresis (MTE). Here, the surfactant assembles into a micelle and attaches to the DNA of interest, providing enough drag to separate the target DNA from others in the mixture.

For longer DNA, like a viral genome, more drag is required. Instead, the Schneider Lab found ways to marry the sieving method with MTE. "You still have the mechanism of drag-tagging, and you now also have a mechanism of sieving," says Schneider. His lab has been working to understand how those mechanisms interact.

You still have the mechanism of drag-tagging, and you now also have a mechanism of sieving.

Jim Schneider, Professor, Chemical Engineering

Their new nanosnag method does two things. It changes the mobility of the viral genome to put it in a place where it's clearly separated from the other non-tagged material. It also has a concentrating effect. The rapid deceleration of the genome when it starts to interact with micelles causes a concentration like that seen anytime something moving very quickly is forced to slow down. Picture the traffic congestion caused by a lane closure on a highway.

"What's surprising is that the addition of a tiny, 30-base fragment of double-stranded DNA has such a huge effect on the migration of a 5,000-base viral genome," says Schneider. "We initially attached the fragment as a way to attach fluorophores to the genome and did not expect any impact on the electrophoretic mobility. But when you dig into the polymer physics, you see why it happens. The short, double-stranded fragment is much stiffer than the genome, and its attachment forces the genome to take a longer, more winding path through the matrix."

The tagging technique also enables researchers to detect only the viral genome, because the nanosnag fragment binds specific sequences. "If those sequences don't exist on a DNA or RNA fragment in a sample, the nanosnag will not attach, and none of this slow-down or sharpening occurs," he says. "So we can confidently discriminate the viral genome from other nucleic acids that might be in the sample."

The new method could be used, for example, to count the number of viruses inside a bioreactor that makes them. Viral bioreactors don't produce a steady amount of virus, due to the way viruses are produced throughout the cell cycle. Current methods for measuring how much virus is in a batch are slow and imprecise. Schneider's nanosnag method, published in Biomacromolecules, provides the biomanufacturing industry with a direct way to quantitate virus, and it's fast.

This project was developed with an award from the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL) and financial assistance from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology (70NANB17H002).

Schneider is actively engaged with pharmaceutical companies to bring the technology to manufacturing lines. One challenge is that bioreactor samples have a lot of cell debris, viral capsids, and other proteins that typically interfere with viral detection methods. The surfactants used as gel-like matrices can help sequester these compounds into micelles so that the electrophoresis is not affected. Determining just how much material the surfactants can handle is an active area of investigation in the Schneider Lab.

Schneider's electrophoresis methods offer a unique advantage for translation to industry because pharmaceutical labs already have standard commercial platforms to do electrophoresis. "If they follow our methods, they don't need to buy new equipment and can enjoy the speed and accuracy benefits right away," he says.

For media inquiries, please contact Lauren Smith at lsmith2@andrew.cmu.edu.